FROM IRISH TO AFGHAN

The early versions of the play Irish Flames were closely based on the book: the eyewitness account of Peter, my Irish half-brother (Robbie in the play). His English mother Meli falls in love with Martin, the leader of the IRA, and saves his life after the IRA has ambushed the Black and Tans who had gate-crashed the 1920/1 New Year’s party at the family house. The Tans return and burn down the house.

In September 2007 the Royal Court said: "This is a warmly received play assuredly written. The play offers a powerful commentary on wartime violence and retribution. We felt the narrative is at times sentimental and tends towards reportage."

The Abbey suggested that it was a lean play for the amount of action.

On December 5th, 2007 the play was rehearse read, for the first time, at the Irish Centre in Hammersmith. Ros Scanlon, the director, and I agreed with the Royal Court and I totally rewrote the play to move the emphasis from the sentimental relationship between Meli and Martin to the transition of Robbie's friend, Conn, from innocent gardener to 'insurgent'. I eliminated some of the reportage by having the RIC Colonel Smyth make his 'Surge of troops and Tans' speech as the first scene.

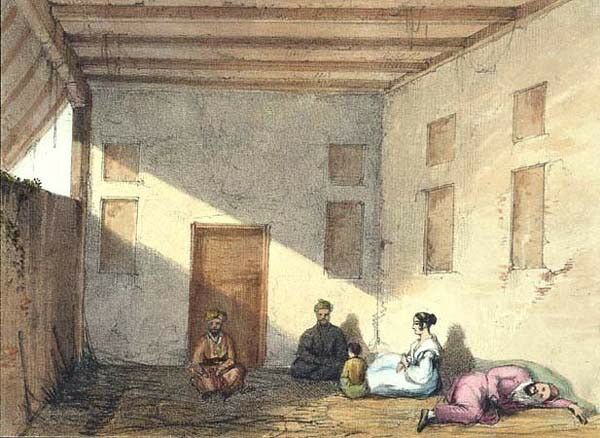

Captain Waller in captivity - by Sir Vincent Eyre

In October 2008, we had a second rehearsed reading at St. Mary's University College. From this, my mentor, James Smith of the "Thick of It" and "In the Loop", suggested the ending was left hanging in the air and asked for an extra scene to be added. Set in 1932 Boston Robbie calls Con a 'murderer' and Con calls Robbie a 'posh Englishman'. Martin, a reporter on the Globe sums up the lessons that could be learnt from the Irish War of Independence, then Civil War, then the Economic war with Britain and asks: 'why do big countries treat small countries as if they own them'. Robbie adds: '‘Peace came about because enemies talked to each other'. Con concludes that: 'war will never end until occupiers leave and men are free'.

The Abbey now said the play 'is a tightly plotted historical drama, with plenty of twists and turns in the action to keep the audience interested. The factor of truth also adds another dimension of interest. The focus on the relationship between Robbie and Conn brings a human element to the play and prevents it from being simply an historical retelling'. They suggested a reworking of first and last scenes, which I did.

The Tricycle now liked the 'post scriptum' and said that 'the author has had readings and encouragement all round so I'm sure he'll get it produced eventually'. The Tricycle then put on their summer of Afghan plays, some of which brought out the points I was making in my own play. My ancestor Robert Waller was held hostage after the Retreat from Kabul in 1842. (See lithograph image above.)

Bombing the Afghans

“The scenes we had to go through, as you may imagine, were frightful; such a retreat, in the depth of winter, without food, clothing or shelter – another whole country under snow!!! The men’s feet and hands were frozen off and they fell in the road by scores, while the enemy pressed on our rear with the impossibility of keeping them at a distance, our guns having been abandoned one after the other, the horses being incapable of drawing them and the hills on every side covered with the enemy’s riflemen, who kept up a constant and destructive fire upon us, while at every check a general rush was made, attended by fearful slaughter, our men being almost incapable of making any resistance.

A few days from the commencement of the retreat completed the destruction of the force - it was a dreadful time as we passed along over the dead and dying, the wounded and frost-bitten of our comrades and friends. No questions were asked, no assistance to the wounded could be afforded, where they fell there they lay to be butchered in our sight by our enemy who spared none except a very few who happened to fall into the hands of the chief men - among who were myself, wife and child - Iwas severely wounded in the action previous to the retreat and have a bullet in my right side now which passed through my arm below the shoulder and before that I had been wounded in the head, but not severely.

Akbar Khan has treated us with much more kindness and consideration than we had reason to expect under all circumstances. He supplied our wants to the best of his ability for we saved not an article or sixpence, having escaped but with the clothes on our backs, and for more than a fortnight we had nothing but these, day or night in the middle of winter, and having been on the bare ground or on the snow. Negotiations for our release have been tried, but without success as yet. I believe, however, that Akbar is willing to make terms if they are not too hard upon him. He has promised to forward this letter for us, and I am going to send it open.”

I therefore added an extract from this extraordinary family letter as the new first scene of Flames of Freedom, moving the surge speech to the end of Act One. I removed the Tans from the play as subsequent scenes illustrated their deeds e.g. the torching of the family house and the torture of Conn. This cut the cast from nine to six.

In February 2010, a reading was held in Birr, Co. Offaly, Ireland. The director noted the similarities of the insurgency (by 'freedom-fighters') in Ireland and that in Afghanistan and concluded that the historical setting of the play could be brought out by back-projections. I have linked in, as examples, a number of back-projections including, in Act One, Scene Three, the Bombing of Afghanistan in 1919 (below) and, at the start of the second Act, the Burning of Cork by the Tans in 1920. This could be enhanced, in Enron style, by incorporating part of the RTE documentary The Burning of Cork.

website designed and maintained

by Hereford Web Design